Departamento de Inglés. I.E.S. Antonio de Mendoza

In the 18th century the pivotal city of Western civilization had been Paris. By the time On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life was published in 1859, the centre of influence had shifted from Paris to London. A city which expanded from about two million inhabitants when Victoria came to the throne to six and one half million at the time of her death. When Mark Twain visited London during the Diamond Jubilee celebrations honouring the sixtieth anniversary of Queen Victoria’s coming to the throne, he observed: «British history is two thousand years old, and yet in a good many ways the world has moved farther ahead since the Queen was born than it moved in all the rest of the two thousand put together.» This rapid growth was mainly owed to the shift from a way of life based on the ownership of land to a modern urban economy based on trade and manufacturing. But such changes were not to take place without many difficulties and much suffering on the part of the working people.

George III, Victoria’s grandfather and King of Great Britain and Ireland, began his reign in 1760. He was declared incurably insane in 1811 (Darwin was three years old). George, Prince of Wales, acted as regent until the death of his father in 1820, when he became King George IV -his extravagance undermined the monarchy. He died ten years later and his brother William IV became king. It seems we are dealing with impure reigns in both cases; addicted to the pleasures of the bed and the table, Victoria’s uncles lived indifferent to the hardships endured by the mass of their subjects. The situation was harsh: public meeting were prohibited, the Napoleonic wars put an end to reform, profound economic and social changes required corresponding changes in political arrangements. The «Industrial Revolution» – the shift in manufacturing that resulted from the invention of power-driven machinery to replace hand labour – had begun in the mid eighteenth century with improvements in machines for processing textiles; steam replaced wind and water as the primary source of power in the following decades. This brought the destruction of home industry in rural communities and made people either migrate to the industrial towns or remain as farm labourers with starvation wages. This began what Disraeli later called the «Two Nations» – the large owner or trader and the possessionless wageworker; the rich and the poor -. In 1815, the conclusion of the French war, with troops demobilized and a fall in the wartime demand for goods, brought what might be called the first modern industrial depression. In addition the introduction of new machines caused technological unemployment.

George III, Victoria’s grandfather and King of Great Britain and Ireland, began his reign in 1760. He was declared incurably insane in 1811 (Darwin was three years old). George, Prince of Wales, acted as regent until the death of his father in 1820, when he became King George IV -his extravagance undermined the monarchy. He died ten years later and his brother William IV became king. It seems we are dealing with impure reigns in both cases; addicted to the pleasures of the bed and the table, Victoria’s uncles lived indifferent to the hardships endured by the mass of their subjects. The situation was harsh: public meeting were prohibited, the Napoleonic wars put an end to reform, profound economic and social changes required corresponding changes in political arrangements. The «Industrial Revolution» – the shift in manufacturing that resulted from the invention of power-driven machinery to replace hand labour – had begun in the mid eighteenth century with improvements in machines for processing textiles; steam replaced wind and water as the primary source of power in the following decades. This brought the destruction of home industry in rural communities and made people either migrate to the industrial towns or remain as farm labourers with starvation wages. This began what Disraeli later called the «Two Nations» – the large owner or trader and the possessionless wageworker; the rich and the poor -. In 1815, the conclusion of the French war, with troops demobilized and a fall in the wartime demand for goods, brought what might be called the first modern industrial depression. In addition the introduction of new machines caused technological unemployment.

But suffering was largely confined to the poor; this period was for the leisure class a time of lavish display. In the provinces, as it is shown in the novels of Jane Austen, the gentry in their country houses carried on their familiar and social concerns almost untouched by great national and international events. Charles Darwin was the son of a prosperous medical doctor, he lived in a respectable family with a leading role in provincial society which could enjoy peaceful holidays on the Welsh coast. His only sad moment was the death of his mother in 1817, but the eight-year-old boy was well cared for by his three older sisters, he was much loved and no sad recollections were left. Erasmus Darwin, his grandfather, was a poet and evolutionary thinker; Josiah Wedgwood – his mother’s father – was the famous potter and contributor to the Industrial Revolution; both of them were key members of the intellectual flowering of the 18th century. This intellectual, freethinking, scientific family atmosphere would have a great influence on Darwin. His place in upper-middle-class Victorian society was granted, he lived apart from the terrible days that working-class compatriots would endure. He went to Edinburgh University to study medicine in 1825 but he soon realized that was not for him. Christ´s College in Cambridge was his next stop, he needed a B.A. degree to become a country parson of the Church of England and he got it in 1831. In his Autobiography, published in 1876, he wrote: «Considering how fiercely I have been attacked by the orthodox it seems ludicrous that I once intended to be a clergyman.» There he met not only the elite social and intellectual milieu that he would join for the rest of his life but also friends for life, like his professor of geology Adam Sedgwick or John Stevens Henslow, professor of botany who offered a 22-year-old Darwin a journey on a surveying ship, HMS Beagle.

The voyage lasted from December 1831 to October 1836. The diversity in human populations stirred Darwin’s intellect constantly, his Beagle writings contain references to the gauchos, Indians, Tahitians, Maoris as well as missionaries, colonists and slaves. He was convinced that humans were all brothers under the skin and a strong anti-slavery feeling was crucial to his developing views about the unity of mankind. This was his family’s viewpoint, they supported the anti-slavery movements of the early nineteenth century. They were ashamed of that slave economy that had begun to develop in the Caribbean in the 17th century; sugar plantations required a combination of strength and lightning speed, they needed strong, quick, durable and uncomplaining hands; what they needed were not ordinary workers but human beasts of burden. And the Empire was to find them in Africa, three and a half million slaves were transported in British ships alone to British plantations. The slave economy in the Caribbean wasn’t just a side-show of the empire, it was the Empire itself. Abhorrence of slavery began to spread as the Enlightenment developed in Europe during the 18th century, societies were formed to end the slave trade and they succeeded in freeing the slaves in the British Colonies by 1833, when the Beagle was travelling the world. The young Darwin missed these mass philanthropic movements in the same way that he was spared the appalling cholera epidemic that swept through Europe from the Middle East in 1832; an epidemic that was aggravated by the dramatizing problem of urban growth and managed to kill 31000 only in Britain.

Five years away from his beloved England was a long time. When Darwin looked about him he could not help but notice how much England had changed. Railways, towns, shops, chapels, factories and churches sprouted everywhere. This was the England of Dickens’s classic tales.

A year after Darwin returned, William IV died. It was 1837, Victoria was only 18 years old and Queen-to-be. As a child, as many aristocratic children of her time, Victoria was subjected to an evangelical regime of prayers and constant self-examination; she was brought up a model of virtue and self-denial. Christian betterment was the driving force of her generation. As a young teenager, in her first visit to Birmingham, she got from the coach a view of the landscape of a British inferno – sooty and sulphurous – and she wrote: «The men, women, children, houses and country are all black. The country is very desolate everywhere. There are coals about and the grass is quite blasted and black. I just now see an extraordinary building flaming with fire, smoking and burning coal heaps intermingled with wretched huts and carts and little ragged children.» This view from her coach was the closest that Victoria got to the bleak reality of smokestack in Britain.

Her coronation took place on June 28, 1838. Being so young didn’t stop her from having the required dignity and she was wise enough to ask for the help she would need. Lord Melbourne, the Whig Prime Minister, was ready to provide this help and managed to make her public image grow.

Three months after the Queen’s coronation, Darwin read An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) by the British economist Thomas Robert Malthus. «Malthus’s intention was to explain how human populations remain in balance with the means to feed them … Malthusian doctrines had come to dominate government policy… The natural tendency of mankind, Malthus said, was always to increase. Food production could not keep up. Yet, there was an approximate balance, he claimed, because the number of individuals is kept in check by natural limitations such as death by famine and disease, or human actions such as war, sexual abstention and sinful practices such as infanticide … It was God’s will that this should happen.» (From Darwin’s origin of Species. A biography by Janet Browne).

Three months after the Queen’s coronation, Darwin read An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) by the British economist Thomas Robert Malthus. «Malthus’s intention was to explain how human populations remain in balance with the means to feed them … Malthusian doctrines had come to dominate government policy… The natural tendency of mankind, Malthus said, was always to increase. Food production could not keep up. Yet, there was an approximate balance, he claimed, because the number of individuals is kept in check by natural limitations such as death by famine and disease, or human actions such as war, sexual abstention and sinful practices such as infanticide … It was God’s will that this should happen.» (From Darwin’s origin of Species. A biography by Janet Browne).

Darwin wrote an entry dated September 28, 1838 in Notebook D; he agreed with Malthus that too many individuals were born. According to Darwin, this implied a war in nature and in this fight the weakest organism tended to die first while the better adapted remained. The repetition of this action over and over again made these organisms ever more appropriately suited to their conditions of existence. Darwin suggested that it was nature itself that made the selecting and he managed not to make any reference to the creator. In one of his letters he would write: «Being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence … it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work.» Here was the essence of Darwin’s theory, which, for the moment, he kept secret.

Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood in 1839. In 1840, Queen Victoria married her cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

The decade of the 40s was a terrible time for Britain, Queen Victoria found a very unstable society which probably was as close to a revolution as it would ever be: suffocating overcrowded industrial cities; hundreds of wretched, defrauded and oppressed hands put together to make money for cotton traders; children doing menial but very dangerous jobs; workers against masters; province versus metropolis. A slump in foreign trade implied that hands were laid off in tens of thousands. Bread was unaffordable, a luxury for the unemployed who blamed the Corn Laws for keeping cheap imported wheat out of Britain. Working-class anger and desperation was close to boiling point. For middle-class reformers the answer was easy, they must get rid of the Corn Laws. (The laws that controlled from 1360 to 1846 – when Sir Robert Peel’s government abolished them – the import and export of corn to guarantee farmers’ incomes. They were disliked by the working classes, because they kept the price of bread high, and by the manufacturers, who argued that little money was left for buying manufactured goods.) But the militant spokemen of the working people didn’t agree, they wanted more. They set out a demand in 1838, ‘The People’s Charter’ was a new Magna Carta for the modern age with its six famous points: the right to vote for all males (women were still out of the game), the secret ballot, equal electoral districts, abolition of property qualifications for MPs (Members of Parliament), payment for MPs and annual general elections.

In this climate of hatred and fear, people had to decide where their loyalty lay. If you were the owner of the great spinning mills, you would consider the Chartists were a mislead mob. If you were the hard-working class, you might want to believe them. However the petition was rejected by Parliament and a huge demonstration in 1839 ended in a bloody confrontation. A last monster Chartist petition, signed by nearly two millions men and women, was brought to London on April 10, 1848. Around 150,000 Chartists would gather for the biggest political rally in British history on Kennington Common but London was prepared to receive them, it was turned into a huge armed camp: guns, guards and cannon were posted at critical sites, even the Royal Family left the city. Fergus O’Connor, newspaper owner, MP and leader of the Chartists, had no choice. Nobody should provoke the troops or the result would be a bloodbath. This ended the threat to the political establishment but the dream of so many working people for somewhere decent to live, enough to eat and for a share of the Victorian bonanza, was as urgent as ever.

1845 brought the potato blight, a million Irish died of the consequences of malnutrition and more than two million emigrated between 1845 and 1855.

The 50s represented a change, a boom, a time of prosperity. Despite having serious problems, the growing sense of satisfaction that the difficulties of the 40s had been solved was in the air. The Royal family showed a middle-class domesticity air and devotion to duty; the aristocracy was discovering that Free Trade was enriching; agriculture flourished together with trade and industry; the conditions of the working class were also improving: restricted child labour and limited hours of employment.

The 50s represented a change, a boom, a time of prosperity. Despite having serious problems, the growing sense of satisfaction that the difficulties of the 40s had been solved was in the air. The Royal family showed a middle-class domesticity air and devotion to duty; the aristocracy was discovering that Free Trade was enriching; agriculture flourished together with trade and industry; the conditions of the working class were also improving: restricted child labour and limited hours of employment.

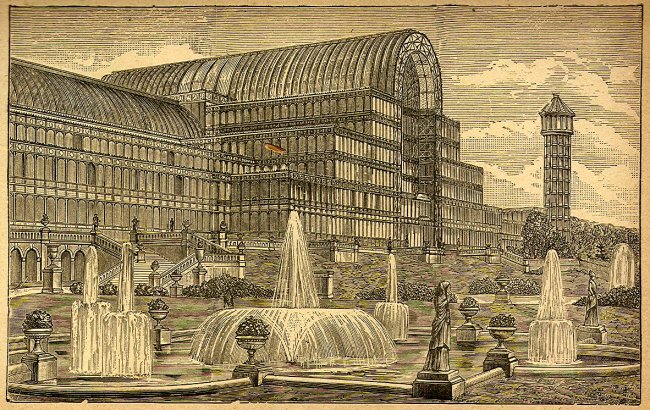

Prince Albert would address his energy to make industrial Britain a better as well as a richer place. He was the moving force behind The Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. The Crystal Palace, a gigantic glass greenhouse built up by brawny labourers in six months and designed by Joseph Paxton, had been erected to display the exhibits of modern industry and science. The building itself symbolized the triumphant feats of Victorian technology (unfortunately it burnt down in 1936). Six million people came to see the show of shows. Prince Albert was the first prince to wear his connection with the world of business as a badge of pride, not shame.

However most mid-Victorian intellectual society was less preoccupied with technology than with the conflict between religion and science. Great currents of change were making their presence felt in Britain. The most popular of Victorian poets, Alfred Tennyson, who had begun seriously to doubt the religious system, wrote his poem In Memoriam as a celebration of his friendship and to express the overwhelming doubts about the meaning of life and man’s role in the universe. This poem was intended to help readers explore the big issues of human existence and the terrible void after death.

Although many English scientists were themselves men of strong religious convictions, the impact of their scientific discoveries seemed consistently damaging to established faiths. Geology, by extending the history of the earth backwards millions of years, reduced the stature of the human race in time. Astronomy, by extending a knowledge of stellar distances to dizzying expanses, was likewise disconcerting. But biology would push Victorian society’s astonishment even further. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life appeared in 1859 and Darwin’s theory of natural selection finally brought the topic fully into the open, and the public, as well as the experts, took sides.

«… Victorians found it nearly impossible to accept the idea of a gradual change in animals and plants, and equally hard to displace God from the creative process. Yet, this volume and the ensuing debate, placed the issue of evolution before the public in a form that could not be ignored. The essence of Darwin’s proposal was that living beings should not be regarded as the careful constructed creations of a divine authority but as the products of entirely natural processes. As might be expected, there were scientific, theological and philosophical objections from all quarters … Even Queen Victoria took an interest… The real challenge of Darwinism for Victorians was that it turned life into an amoral chaos displaying no evidence of a divine authority or any sense of purpose or design.» «In truth, the furore generated by evolutionary ideas pulled apes, anatomy, polemic, fear, disgust and sensationalism into a single debate. Benjamin Disraeli, the future Conservative prime minister, exposed the unease of his contemporaries in 1864 when he asked ´Is man an ape or an angel?´ He went on to assure his audience that he was on the side of the angels.» (From Darwin’s origin of Species. A biography by Janet Browne).

«The Woman Question» was not a less important issue than evolution or industrialism.

Queen Victoria had mixed opinions which illustrate the different aspects of the problem: she believed in education for her sex; she opposed the movement to give women the right to vote – «This mad wicked folly of women’s rights … forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety» -; she was conscious of the role of women once they were married – «There is great happiness … in devoting oneself to another who is worthy of one’s affection; still men are very selfish and the woman’s devotion is always one of submission.» «Still the poor woman is bodily and morally her husband’s slave. That always sticks in my throat.» – but Victoria, despite being a woman and the Queen, accepted that because «God has willed it so».

Let’s not forget that at this time a woman lost all her possessions to her new husband, could be beaten with a cane (as long as the cane was not thicker than a thumb) and could be locked up for refusing sex. Two of the great critics of the Victorian conventions of marriage were John Stuart Mill (writer and thinker) and Harriet Taylor (writer and poet). They wrote The Subjection of Women, a book which Mill published in 1869 after Harriet’s death. The book was concerned about happy and equal marriages, women’s pay according to their labour and women’s right to vote. They believed that education and law would enlighten and protect women.

Florence Nightingale, a British hospital reformer and founder of the nursing profession, volunteered on the outbreak of the Crimean War, in 1854, to lead a party of nurses to work in the military hospitals. Great as it sounds, she had turned down Mary Seacole’s services because she didn’t fit the profile of middle-class nurses: Mary was West Indian. Seacole was a largely self-taught excellent nurse who got herself to Crimea with her own funds. Elizabeth Garrett, a surgical nurse who looked carefully at surgical operations and who trained herself by cutting body parts in the privacy of her bedroom, was bold and good enough to take the hospital’s medical exams and come top. Florence, Mary, Elizabeth, Harriet, many female writers and one quarter of England’s female population had jobs, however most of them were onerous and bad-paid. There was a very long and harsh path to walk, but women were on their way.

Prince Albert contracted typhoid in 1861 and died. His death threw the Queen into a paroxysm of grief: «My life as a happy one is ended. The world is gone for me … it is henceforth for our poor fatherless children, for my unhappy country, which has lost all in losing him.» She was no longer the accustomed strong-minded queen. The so-called «late period», the 70s and 80s, was for many people a time of serenity and security. Others couldn’t help but see trouble ahead: the relation with the Irish; the emergence of Bismarck’s Germany; the serious competition that provided the United States after their recovery; the growth of labour as a political and economical force or a third of the able-bodied men unemployed.

Darwin died at home in April 1882, aged seventy-three. Janet Browne writes that he had enjoyed «being a traveller, husband, father and friend, as well as a naturalist and a thinker»; he had «disliked public disagreement» but «above all else, he was indisputably an author. As an old man, looking back over the arguments that had surrounded him, he ruefully acknowledged the way in which Origin of Species had dominated the era. ‘It is no doubt the chief work of my life’, he wrote in his Autobiography. ‘It was from the first highly successful.'»

Bibliography

- Browne, Janet. (2006). Darwin’s Origin of Species. A Biography, London, Atlantic Books.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (2001). The Oxford History of Britain, New York, Oxford University Press.

- Schama, Simon (2006). A History of Britain. The Fate of Empire, 3rd volume, London, BBC Books.

- Elton, Geoffrey (1994). The English, Oxford, Blackwell.

- Abrams et al. (1986). The Norton Anthology of English Literature, New York, Norton.